Folk devils and saints in Scottish folk magic occur time and time again. Folk devils are tied to stories in our land and demonise our past folk traditions. Saintly spirits (along with folk devils) are called up for healing, cursing, childbirth, protection, and everyday life. Other stories tell how we could call upon them to place ourselves into the devil’s care as a form of initiation. Folk devils and saints are the agents in a lot of operative folk magic. Scottish Folk Magic Practitioners embrace them as part of a syncretic approach to folk magic quite rightly as sometimes this is all we are left with (or is it?). A heretical standpoint to a lot of Abrahamic religions but our peoples folk magic is no less valid a way of interacting with the world as direct prayer, forms of ceremonial magic or otherwise. All well and good you might think. However, we need to be ever critical. When we explore how our spirits became called saints and devils as part of the reformation and colonisation of Scotland, we start to see a very real issue. The term Folk devil become a phrase used by those seeking to oppress the folk traditions of a people – in simple terms- what we once found helpful and part of our way of life, elites (like the ruling class, clerics, and the church) labelled heresy and demonic. I think when it comes to Scottish Folk Magic and a reclaiming of a tradition, we can’t be idle when it comes to exploring the impact of history like this.

This article only explores a couple of Scottish folk devils and saints. I’ll attempt to demonstrate why its important to examine them for pagan and folk tradition and cultural survivals. I really want to draw on a few examples of where interesting research and insight has been offered. I hope it will encourage others to explore deeper connections they have to their own folk devils and saints. Its providing a road map for other Scottish Folk Practitioners based in Scotland and the Diaspora. A method. A context as to why revaluation of these things is important. I hope you will reflect on what you read and a future pause for thought when you hear and use these terms. Perhaps this can start as a beginning to move through and beyond these ideas to something different.

Surviving paganism and folk traditions

“In reference to the gradual disappearance of these spirits, fairies, etc., the same gentleman makes the following quaint remarks : — “The brownies, fairies, and other evil spirits that haunted and were familiar in our houses, were dismissed, and fled at the breaking up our Reformation (if we may except but a few places not yet well reformed from Popish Dregs) as the Heathen Oracles at the coming of our Lord, and the going forth of His disciples ; so that our first noble Reformers might have returned and said to their Master, as the seventy once did: ”Lord even the devils are subject to us through thy name” And this restraint put upon the Devil was far later in these northern places than with us, to whom the light of a preached Gospel did more early shine.”

Rambles in the far north 1884 R Menzies Fergusson. 2nd ed.

The above quote is a testament to the impact Christian colonising had on Scotland. It’s a little terrifying to read personally. Let’s focus on our folk devils with this quote in mind.

A great and well know example is found on Orkney, in the Tale of the Big Black Wollowa. The original story (known in a rather problematic term of the “witches’ charm”) was recorded by Walter Traill Dennison a farmer and a folklorist. He was a native of the island Sanday and published the story of the charm in the Orcadain Sketch book published in 1880 in Kirkwall. The eagle eyed amongst you will notice 1880 is a date after the highland clearances. Orkney didn’t escape these. We need to be mindful these surviving stories are from people who didn’t leave Scotland. Old folks who stories would die with them, if not conserved, but equally had suffered a huge cultural trauma. Easy pickings for an elite academy as they came to gather up this fading history with bribe or persistence.

A comparatively well-off Sanday farmer, Dennison combined local orature, folk poetry, his own verse, and his own short story writing into an anthology of ‘Traits of Old Orkney Life’. The book is the first published work of what Dennison called the Orkney dialect, coming at a crucial linguistic moment when the Orkney Norn – of which only a few scraps of written text survived – had comprehensively merged with the incoming Scots language to form the variant of Scots still spoken, to a greater or lesser extent, in the islands. The below is taken from an Orkney Anthology selected works of Ernest walker Marwick. Another eminent Orkney folklorist. On page 343 of the anthology of ernset work we find mention of “an example of diablerie which does not seem to fit completely into either Norse or Scottish tradition”:

“…the person wishing to acquire the witch’s knowledge must go down to the seashore at midnight, must as he goes turn three times against the course of the sun, must lie flat on his back with his head to the south and on the ground between the lines of high and low water. He must grasp a stone in each hand, have as tone at the side of each foot, a stone on his chest, and another over his heart and must lie with his arms and legs stretched out. He will then shut his eyes and slowly repeat the incantation

O’ Mester King o’ a’ that’s ill,

Come fill me wi’ the Warlock Skill,

An’ I shall serve wi’ all me will.

Trow tak me gin I sinno! (if I shall not)

Trow tak me gin I winno! ((if I will not)

Trow tak me whin I cinno! (when I can not)

Come tak me noo, an tak me a’,

Tak lights an’ liver, pluck an’ ga, (ga are internal organs)

Tak me, tak me, noo I say,

Fae de how o’ da heed, tae da tip o’ da tae.

Tak a’ dats oot an’ in o’ me.

Tak hare an hide an a’ tae thee.

Tak hert, an harns, flesh, bleud an banes,

Tak a’ atween the seeven stanes,

I’ de name o’ da muckle black Wallowa!The person must lie quiet for a little time after repeating the Incantation. Then opening his eyes, he should turn on his left side, arise, and fling the stones used in the operation into the sea. Each stone must be flung singly; and with the throwing of each a certain malediction was said.”

Sadly, we don’t have a record of the malediction given as the stones were thrown.

Marwick suggest this charm has been added to by Dennison. Suggesting he “improved” the charm by adding in certain sentences when he found the verse to be “clumsy and incomplete”. (p344, ibid). Marwick was also a reasonable expert on Norn and poetics and he found the lines “O’Mester King o’ a’ that’s ill, come fill me wi’ the warlock skill” to have to modern a sound as compared to the following lines. I’d also add “an I shall serve wi’ all me will” to that list of additions by Dennison. He also goes onto add Master king ‘ a’ that’s ill” is a sophisticated conception of the devil which blatantly doesn’t chime with the use of the word Trow. A Trow being a word like Troll in Norse, Scandinavian and Anglo-Saxon and very much unrelated to the devil (in a folk way of understanding) but in general population, as culturally we shifted toward viewing life in a Christian way, I can see how it turned into a version of a folk devil. Our Trows became their devils after all …

Exploring the instructions however, we have some very clear indications this is an older charm. The liminal space of midnight and between ebb and flow. The widdershins or non-sunwise turn would suggest an undoing of a natural order. The seven stones are curious, I’m surprised it’s not nine. If you are pledging all of something you would pledge nine of the things. Nine is also the number of parts of the Norse conception of what we call the soul today. If this is the case, what parts are we holding back? Seven is still a significant number in terms of folk magical practice relating to Scotland and Scandinavian practice. It has a biblical heritage like relating to the world being created in seven days or the seven planets. Anyway, I digress.

Removing the additional lines would leave us with:

Trow tak me gin I sinno! (If I shall not)

Trow tak me gin I winno! ((If I will not)

Trow tak me whin I cinno! (When I cannot)

Come tak me noo, an tak me a’,

Tak lights an’ liver, pluck an’ ga, (ga are internal organs)

Tak me, tak me, noo I say,

Fae de how o’ da heed, tae da tip o’ da tae.

Tak a’ dats oot an’ in o’ me.

Tak hare an hide an a’ tae thee.

Tak hert, an harns, flesh, bleud an banes,

Tak a’ atween the seeven stanes,

I’ de name o’ da muckle black Wallowa!

The term wallowa is where we now focus our attention. Edmonston (1809) in “a view of the ancient and present state of the zetland islands” describes wallowa to mean devil. Jamieson (1879) in “An Etymological Dictionary of the Scottish Language” follows along similar lines but offers us wallowa as an interjection of sorrow or disgust. The devil is glossed out as “the sorrow”. Earlier writers like Lindsay in “the works of Sir David Lindsay” (1931) suggest witches gather with “with mony wofull wallaway” which is resonate with the idea of sorrow. However, Marwick goes on to explore how wollowa could be related to the idea and corruption of the Norse Volva which means prophetess. Again, this doesn’t seem to fit given the nature of the Volva and the nature of Trows. A lot of interpretation going on here, but the discussions focus on Norse influenced spiritual figures.

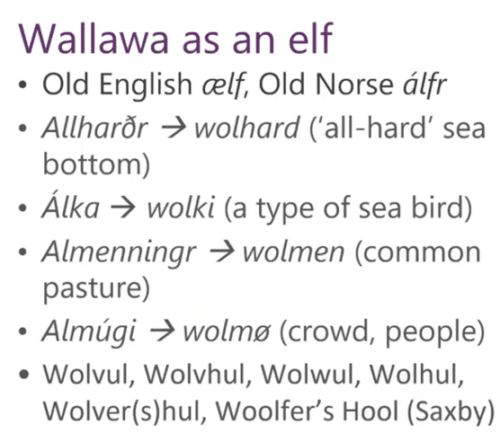

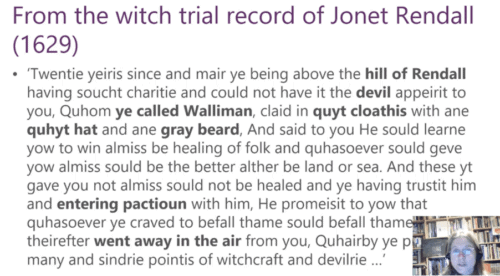

Modern day scholarship has shed new light on this. At the Performing Magic in the Pre-Modern North Conference 2021. Ragnhild Ljosland explores this very issue and gives us new insight. You can start the video around 7 mins in to hear the story of Jonet Rendalls testimony. Ragnhild goes onto to explain how Wallowa might be related to a term of Aelf. I’ll pick this thread up after the jump.

If you haven’t time to watch the video Ragnhild explains how Norn words were changed to scots words. An example of how the Norn words were changed in the local dialect is in the image taken from the video below.

Ragnhild goes onto discuss the Witchcraft Trial of Jonet Rendall. Jonet describes someone she calls the Walliman. Her description is reminiscent of how we describe the Good Neighbours or the Sìth in Scottish lore. I.e. “clad in white clothes and with a hat and gray beard”. This Ragnhild contrasts with the description from other folks’ testimonies on the island of seeing an “old grey whiskered man dressed in old grey clothes patched in every conceivable manner with an old bonnet in his hand and old shoes of hide tied to his feet” who passes a dire warning for disturbing a cairn burial. A note, these descriptions are very similar to those found of the old grey magician by George Macpherson book of the same name. Of note the grey wanderer is an epitaph of Odin.

A wild witch chase the case of Kate Nicneven

I have written about this elsewhere on the site and you can read the full story there. In short, a woman burned at the stake, Kate Nicneven is a, perhaps, the real story behind the goddess Nicneven. The idea of her as a little known goddess survival from pagan times seems to have originated from burlesque poetry and other sources for Nicneven has led to some practitioners of witchcraft to equate Nicneven as the Scottish Queen of witches, a little like a Scottish Hecate. In the article I explore why this probably isn’t the case.

St Columba – the originator of the Eolas (knowledge)

Turning our attention to saints for a very quick moment. Countless research has been done on the early “Celtic” Catholicism. This Catholicism syncretised with older beliefs and contains folk magic and pagan survivals. These continued up to (and beyond) the reformation, finally wiped out mostly in the 19th century during the devotional reformation. We know some saints overwrote previous spirits found in wells, groves, and landscape features. We also know how some saints became explanations for pagan ancestral spirits. I find it interesting a lot of saints were magicians (St cyprian and saint Patrick come immediately to mind. If you read their stories, they do a lot of, what might be called magic or witchcraft).

In Scotland, one mechanism used to explain how magic spread to the folk was via a Saint. The story goes St Columba, a very well-known saint in Scotland spread the knowledge of Eolas because he was trying to help the poor. Eolas (pronounced jäyl-ass– kinda) is a form of Scottish folk magic. W. Mackenzie in “Gaelic Incantations with Translations” provides a story about how he did this:

“St Columba had two tenants. One had a family and the other had not. The rent was the same in each case. The one who had no family complained to the Saint of the unfairness of his having to pay as much rent as the other considering his circumstances.

The Saint told him to steal a shilling’s worth from any person, and to restore it at the end of a year. The man took the advice, and stole a small book belonging to St Columba himself, and thereafter he proceeded to the Outer Hebrides, where he permitted people to read the book for a certain sum of money.

The book was read with great avidity, as it contained all the “Eolais” composed by the Saint for the curing of men and cattle. Thus, it was that these “Eolais” came to be so well known in the Western Islands.

The farmer went back to St Columba at the end of a year, having amassed a considerable fortune, and restored the book. The Saint immediately burned the book, so that he himself might not on its account earn a reputation which he thought he did not deserve”

w.m Mackenzie Gaelic Incantations and their Translations

Colonial Folks Devils and Saints- What does this all mean?

In the example of the big black Wallowa, this provides evidence of pagan survivals in witchcraft trial testimony and folklore. It’s all tied up in time & etymology. The term Folk Devil to refer to the muckle black wollwa is far from sufficient. As practitioners we need to really step away from Umbrella terms for things we want to embrace but won’t do the leg work to explore more fully. In this trial testimony and subsequent charm, we might be looking at a pagan survival relating to Norse world views and practices. This is important because Norse magic and world views have their own tradition. This also helps to shed some light on the magical practices of Orkney, which we know so little about .To then just call this Folk witchcraft seems negligent to me. It literally erases the cultural flavour of an entire islands folk magical practices if we are simply to say “oh this is how to become an initiate into witchcraft and worship the folk devil.”

Our folk devil is a merely an amalgam of spirits and folk myths – not a single idea but a myriad of things. A character masking something more. We can and perhaps should argue the term “folk devil” is a term used to colonise and oppress a folk religious belief used by our christian and reformation minded colonisers.

If we were to stop at the wallowa being a folk devil we are only realising part of the story, part of the mythos and part of the way we have approaching spirits like this as folk practitioners. In this example we know, if the wallowa be an Aelf or one of the good neighbours more about who this spirit might be, why you might want to offer to it yourself and others and what the outcome would be.

In the case of Kate Nicneven – conflating dead woman who gathered about them a reputation with the queen of witches. It’s another trap for folk practitioners looking to historical evidence and an example of another way for the elites, in this case well known poets, to overwrite non elite and local story and deliver a new Spirit into folklore history. We know, almost all witches burnt at the stake were just guid folk and they were also Christian folk. I wonder how Kate might feel that she is now a representation found as the head at the charge of the wild hunt.

In the case of Saint Columba and the story of Eolas, here we have an actual attempt by the church to provide a lineage to magic through their saints. Saint Columba is very well known in Scotland and this story is interesting. Surely, by the saint allowing the Knowledge to spread like this it sanctifies it. It removes any devilry. I find potential spiritual violence can be found in approaches like this. Especially when we explore the Goetia and the practices found therein. Personally, I find the suggested mechanisms and approaches detailed in the Goetia incredibly Christian and almost akin to spiritual violence. The Scottish Folk and Trolldom Practitioners I think are good do not operate like this at all. Sadly I know a few who operate in this exact way.

Anyone working as a Scottish Folk Practitioners knows we do not command in the name of God we operate in a reciprocal and equity-based way to the human and non-human worlds. Equity consciousness is a foundational stone (if not the most important foundation) of folk magic, to remove this equity based relational way of being from our people, as was done through the reformation and colonisation led us into a world of exploitation of natural resources, people and in no small part has led us to where we find ourselves – at the edge of a climate crisis today.

The tale of saint Columba is a story of commodification of folk magic. What a trick to wrap up knowledge and equate it with money suggesting you can use folk magic knowledge to pay your bills. A tale commodifying folk magic from its very beginning. Its quietly terrifying how many people probably don’t even notice this commodification taking place as it’s become quite the norm.

A few further thoughts about the impact of the colonial folk devil

Our folk devils and saintly masks are thin.

Those with the eyes to see know their guises are a thin veneer – wrappers of an identity rooted in pagan survivals and folk traditions. As often happens beliefs and spirits of the non-ruling class, are often overwritten, combined with, or removed. A lot of surviving written histories only speak about the beliefs of the elite.

By removing an older more relational way of relating to the world the reformation successfully detached our connections to pre-Christian thoughts and the pagan survivals within the “Celtic” catholic church. This enabled and led to the murder of thousands of people during the witchcraft trials laid the groundwork for future exploitation, forced emigration through the clearances, and a loss of a way of relating to the world. This overall was engineered by the ruling class in the voice of reason, science, and the enlightenment. It justified future materialism and exploitation of nature and people. Leading to the rise of materialism and capitalism and the climate crisis we are in today.

It is not only the people who are so maltreated. We see this pattern inside of herbalism constantly. Plants became holy and unholy. Saints’ names representative of a plant’s nature, the older pre-Christian stories hidden behind the mask of saint or common name like devil’s nettle.

We all know the story of St John’s wort, but how many people know its relationship to Odin? Botany science has become an elite pursuit. In the march toward scientific categorisation our common Gaelic, Scots and other names were replaced by Latin. Greek myths became the tale for how these plants worked – ignoring the local stories of the non-elite folk. Our folk. Us.

Just in the same way our local spirits were called the folk devil science turned our plants into taxonomies.

We lose the connection as we lose our language.

This continues unabated outside of the Scotland and Britain.

Colonised cultures and indigenous spirits become the folk devils and saints of the settlers. indigenous belief is forced out through violence and economics.

It’s still happening today.

Thank you for allowing me a short stand on my soap box about these issues. You might be thinking what all the fuss is about … I personally think we can do better as Scottish Folk Magic practitioners to not follow the heard of popular opinion.

I always say, “the landscape is the book” and I add “we just need to get out there and read it”. Exploring the tales of place, people and their devils and saints can really help focus on what’s important and help undo some of the damage running riot. This in turn can help inform how we operate in the world we are in and perhaps and ever hopefully encourage reciprocal and equity consciousness to return.