Newsletter Subscribe

Enter your email address below and subscribe to our newsletter

Enter your email address below and subscribe to our newsletter

Exploring Scottish Folk Practices and Traditions

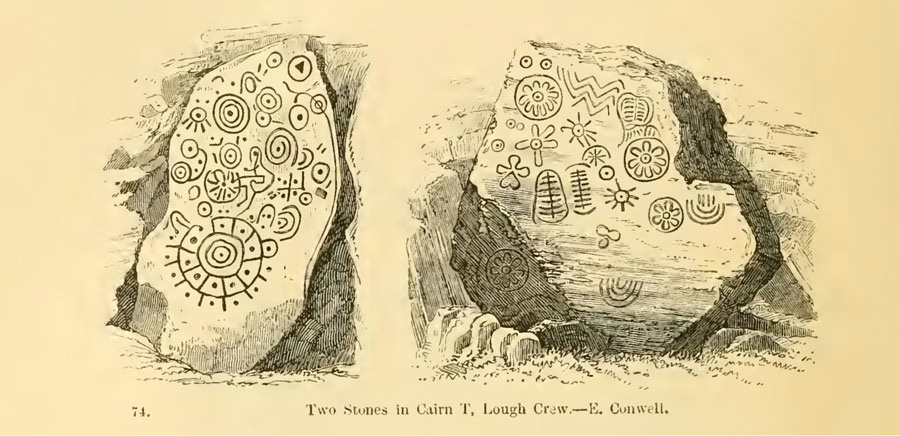

When the light of the sun of this day shines into the inner chamber of Sliabh na Calli (The Cailleach’s mound). By solar reckoning, the year is exactly half. Half day, half night. At one exact moment, the world balanced on a pin head. Everything in equal measure, fifty-fifty, resting in perfect balance, a pause. A breath. Exhale. The cry of the cuckoo calls out. Release. We move on to the lighter times. The spring equinox La na Cailleach is here.

In neopagan and Wiccan circles the spring equinox has become related to Easter. Termed either Ostara or Eostre. It is the spring celebration. A lot of the neo-pagan and Wiccan thinking around these links is written about elsewhere. So I won’t be rehashing it here. For those that follow, perhaps a different path, such as folkloric practices. This day might seem different.

Allow me to introduce you to some of these ideas. Some Scottish folk practitioners know the spring equinox by the name of “ladies day” or the La na Cailleach. We acknowledge it as the old new year, the time to hunt the “Gowk” and link it to April fools day. It may also link our cultural heritage to Black Donald, the Guidman or Old horny. Sometimes known as the devil, by way of the Harlequin and fools. More on that later, first some background.

The earliest recording of a new year celebration is believed to have been in Mesopotamia, c. 2000 B.C. and was celebrated around the time of the equinox, in mid-March. The Romans changed this and added in months here and there. Julias Ceaser’s nominated January the 1st to become the officially sanctioned new year celebration in Rome. This would bring it in line with the Roman Consulate dates and their elections. It also aligned it with the civilian year. This moving of the calendar became a hotbed of religious contention over the years.

In medieval Europe, for example, the celebrations accompanying the new year were considered pagan and unchristian like. In 567, the Council of Tours abolished January 1st at the beginning of the year. At various times and in various places throughout medieval Christian Europe, the new year was celebrated on Dec. 25, the birth of Jesus; March 1; March 25, the Feast of the Annunciation; and Easter.

In 1582, the Gregorian Calendar reform restored January 1 as New Years day. Although most Catholic areas adopted the Gregorian calendar almost immediately, it was only gradually adopted among Protestant countries. The British, for example, did not adopt the reformed calendar until 1752. Until then, the British Empire —and their American colonies— still celebrated the new year in March. Just imagine how confusing all this was for people with no internet and printed written word one colonel doing something very different from another until word spread. Still today there are still places in Russia where this date is still celebrated as the new year interestingly enough.

The date of the 25th of March ties it to the feast of the Annunciation, significant to those of a catholic or Christian persuasion. This festival is exactly nine months before Christmas. The time when Mary was visited by the Angel Gabriel and the immaculate conception was announced. This day became known as Ladies day. It also ties it into the start of the modern tax year on April the 6th. The old new year, celebrated with a week of feasting, lasting up until April the 1st which, also links it to April fools day.

Ladies day occurs on the 25th of March, near the spring equinox and is associated with the feast of the annunciation and the Virgin Mary. Famous in Scotland as a Patroness of wells and fountains. The Virgin Mary also had a nut associated with her. It was termed the nicker nut. It was considered a great charm against illness and strife. Even more so if a silver cross was inlaid into it. These nuts would be washed up on the shores of western Scotland, Ireland and Orkney. They had a white smooth marble like appearance. Known as Molucca beans or Virgin Mary nuts (Wallace, 1693).

“All his Cows gave blood instead of Milk. … One of the Neighbours told his wife that this must be Witchcraft, and it would be easy to remove it if she would but take the White Nut, called the Virgin Maries Nut and lay it in the Pale into which she was to milk the cows”

w.Sc. 1703 M. Martin Descr. W. Islands 39.

This day, more importantly, not only for spring cleaning it is also associated with the Cailleach. (It’s funny how often the Virgin Mary, Bride and the Caillleach happen to be mentioned together). It’s said on this day (the 26th the day after the calendar date for the spring equinox in the Hebrides) the Cailleach would give up beating back the spring growth and grass and throw her mallet under a whin (Holy) bush. A sign that the better weather was on its way.

Dh’fhàg e shios mi, dh’fhàg e shuas mi;

Dh’fhàg e eadar mo dhà chluais mi;

Dh’fhàg e thall mi, dh’fhàg e bhos mi;

Dh’fhàg e eadar mo dhà chois mi!

It escaped me down,

It escaped me up

It escaped me between my two ears

It escaped me tither

It escaped me hither

It escaped me between my two feet

The Cailleachs Lament

Taken from Grant (1925) Myth, Tradition and Story from Western Argyll, p5-6.

Yet, this date is also the start of the stormy weather in Scotland. Known as “a Cailleach”. Which, would relate well to some of the folk tales about the Cailleachs attributes. The term “Cailleach” is also used in some places in the North for the first week of the month of April (Banks, 1939). These “a Cailleach” storms could sometimes last up to six weeks. From the spring equinox date this, interestingly enough, would take us up to Bealtuinn. These storms were welcome as they would deposit a lot of seaweed on the shores. Providing sustenance for everyone and fertiliser for fields. Fishermen were less inclined to welcome the storms and would give offerings to the sea to Shony (more than likely St John) to ensure calm days. Perhaps it is the storms and their appropriations that this date relates to rather than a bigger festival to the Celts.

You can read more about this aspect of it at Tairis.co.uk

Shifting tack, we have the cuckoo day, also known as a gowk [1] day and Aprils fools day. Both are associated with this time of year. In sayings such as “in the month of April the Gowk coming over the hill in a shower of rain” but also in Aprils Fools day itself. In Scotland, April fools day is known as “Cuckoo Day”. People would send the more gullible, or honest and trustworthy, on what was affectionately termed a Gowk Hunt as it was Là nan car, the day of tricks. (Banks, 1939)

Sending someone on the Gowk Hunt means sending them to chase after the cuckoo, a euphemism for a fools errand. Folks are sent on a merry chase these aren’t just small tricks. For instance, someone may be given a letter and tasked with delivering this to someone a few miles down the road. On receiving the letter the recipient opens it up and reads the message:

“This is the first day of April,

Hunt the Gowk another Mile”

Understanding the coded message they would tell the person delivering the note, with solemn tones, they can’t do what the note asks. They would suggest such and such over yonder might be able to help. So they write another note with the same message and send them again on their way. Ad infinitum, until some kind soul, takes pity on them and breaks the chain.

Why hunt the Gowk? Well the Cuckoo, or Gowk, arrives in Scotland around the spring equinox. Trying to catch the sound of its song is said to be a fools errand. The cuckoo or gowk moves so secretly about the woods flitting from tree to tree. You can never find its location from its last call. The call of the male cuckoo is, of course, a love song to his mate. It strikes me there might be a deeper meaning to this chase of the cuckoo in spring. Perhaps it was game lovers played in the woods? Maybe it’s an allegory for fools falling in love, or is it a foolish man who follows the ideals of love? None the less, this sound would truly mean the arrival of spring for the Scottish people. The cuckoo as its herald and the cuckoo’s song the soundtrack of the Old new year.

It’s important to note. In a lot of Ordnance Survey maps of Scotland, you will see reference to Gowk stanes and Gowk hills. For instance, there is a gowk hill in Gorebridge and entries for many a gowk stane all over Scotland and some in England. For this to be described in the landscape of maps and the words in our geography suggests to me there is more to this folk tradition and tale. Something that sits outside our current understandings of the spring equinox. This might help us understand what it meant for Scotland’s people. It’s something important enough to mark it out in the cartography. To me, that’s a big deal.

As a side note, it’s always struck me as interesting that eggs are a big feature of easter. Where did this come from? We have a very tenuous link between eggs and cuckoos which might shed some light on it. We probably all know that the Cuckoo lays its eggs in another birds nest. The cuckoo chick hatches first and kicks out all the over eggs from the nest it was laid in and then gets all the attention from the birds who hatched it. Growing big and strong and then going its own way. Like the changeling sith/sidhe baby of the bird world, I guess. Could this be where the link to eggs appeared from? Who knows!!

This brings me to my last idea. For me, there has always been a link between the trickster and the fool. There is a link between the role of the fool played in the mystery and passion plays with the devil. The fool, in the mystery plays, is actually a rather smart trickster. Playing dumb but ready to take you unawares. The clown in mummers plays has the power to change the course of the story. Sometimes acting in the resurrecting role. The fool can be a fool or a machiavellian type, perhaps a bit like our friend the cuckoo?

According to the work of Ronald Hutton and others (Anon. 1902; Lot, 1903; Grisward, 1981, 183–228; Rey-Flaud 1985, 89) this trickster character, known as Hurlawayne in Northern England was perhaps the leader of the cavalcade of the dead across the night sky. He was represented by the Harlequin. A trickster like our friend the cuckoo, in 16th century Italy. Some have associated the hellequin/Hurlawayne/harlequin with Odin, Diana, Nicneven, Hekate and others. Later this figure became the Devil himself. Leading the witches Sabbath across the night sky (Lacuteux, 2011). Well, perhaps …

Why might this trickster be about at this time of year? Is it because its new year? In Scottish tradition, any change was associated with a risk of danger. It became a liminal time, a time where the sith/sidhe might be aboard. Perhaps for Old New Year, similar fears and appropriations for these abounded. Is the trickster trying to catch folk unaware at the old liminal time? Or is the call of the trickster cuckoo leading fools astray, deep into the woods? Is it a fool’s errand to ever try to catch the devil? Are you a fool for celebrating Old New Year? Or Are you a fool for believing in such thing? Or is it only a fool who would dare go where the devil calls and see what may be learnt?

There is a lot more about the spring equinox than derivative writings discuss. The equinox might relate to the tale of the Cailleach throwing in the towel with one last gasp of stormy weather. Perhaps her 8 hags of the winds are out doing as much as they can but, she herself, has finally given up? For me personally, she truly gives up the goat at the start of summer or Bealtuinn, but she is always present historically, in one way or another throughout every festival throughout the year. The idea of a gowk stone related to Celtic ideas is tenuous. But in gogarburn in Edinburgh, there is the Gogar stone there is also a gowk stane road outside Stirling. Gouger may relate to Cog, a Celtic word for Cuckoo. However, there is very little other evidence to link any celebration of the spring equinox back to the celts or other older Scottish traditions. For this and experiential reasons, I think this date represent the storms that are raised at this point. That is except the link to Sliabh na Calli.

Perhaps the tales of fools cuckoos and spring is a later tale? Maybe not. Perhaps its only my own interpretation. Perhaps it’s a lesson of the spring fool being misled by the tricksters around him. Led on a merry chase to who knows where. Perhaps we are all a bit like this fairy led wayfarer, hunting the gowk as we progress through life looking for a goal that we can never find? Chasing an impossible dream, love or an illusion of truth? Until someone or something alerts us to this being the case showing us for the fools we are. Perhaps this is the idea of the trickster and fools relationship. What appears dysfunctional on the surface is a most constructive relationship. The lesson may be hard won and clothed in the naivety of shame but in the end, we are wiser for it.

[1] Gowk derives from the Old Norse ‘gaukr‘, a cuckoo. Other explanations and origins for the term are also found. The word derives from Anglo-Saxon (Old English) ‘gouk‘ and was replaced in the south and central England by the French loan word ‘coucou‘ after the Norman Conquest. The cuckoo family gets its English and scientific names from the call of the bird. The Scottish Gaelic names are Coi: Cuach: Cuachag (poetical name): Cuthag. The Welsh for cuckoo is cog.

References: