Introduction

I introduced a series of writing exploring the role of the oft neglected dead in Scottish folk magic. If you haven’t read it I suggest you have a wee read. It sets the tone of the rest of the series. Due to the amount of lore and other related bits of information this article is quite dense. A fuller exploration of the subject of funerary customs, death and folklore requires more writing than I feel I’m capable of in a web format. (and maybe more than you’d like to read- It needs chapters). To keep the flow a little easier I haven’t referenced academically but written the odd note here and there which you’ll find when you click on > [footnote] These are the footnotes. I’ve hopefully managed to find a way you can read them as you go along and cut your brain load [/footnote]. I also have highlighted relevant reading as I’ve gone along and happy to discuss sources if you’re interested.

Nowhere, even in modern times, do religious ritual and custom retain a stronger hold on the majority of mankind than at the crisis of death and burial.

Migration, exploration and invasion. Cultural interplay has provided Scotland a rich diversity and depth of folklore. Before the influence of the kirk and the dead’s exile to formalised graveyards the Picts, Celts, Norse, Roman, Viking, Anglo, Saxon and others left deep-rooted beliefs. These philosophies shaped a unique form of folklore relating to the dead born from this melting pot.

The Liminal Dead and the Daoine Maithe.

Return of the dead, its corruption and putrification is a common unifying anxiety. Disease, evil, madness, revenge, curses, blighted crops and destroyed livelihoods are associated with them in many societies both modern and historic. On the reverse, the dead are associated with tutelary spirits, genii loci and deity. For example, a Gaelic exemplar of ancestor turned deity is the tale of Donn. The first of the Milesians to die in Ireland and become Lord of the Dead. His Red Riders and a boat ferrying the dead to his house ,Teach Duinn, at Samhuinn, an appropriate entourage. Other ancestors became genii locorum. Their tales, long forgotten, can be found buried in the Scottish landscape. Hidden in names of towns, rivers, munros and glens.

The way we conceive of the dead today is not the same way as our ancestors. The dead were moving, roving things that could eat, fight and fuck. Thinking changed. The living dead were reduced to appearances in dreams, phantasms and at times demons by an active Kirk. In Scotland, the repository for this lore became the Sidhe, the daoine maithe (good folk). The burial mounds of our ancestors Sidhe mounds. Fairy faith a repository for all things that couldn’t be taken into Christianity’s increasing ideological expansion [footnote] I feel Purgatory and saint worship was a definite attempt at adopting some of the earlier beliefs of ancestor veneration the church needed to compete with. [/footnote]

Our ancestors divided the dead into different distinctions. We will focus on two of these – the restless and the peaceful dead. The intervention of people through folk rites and/or fate moved the departed between these categories. For example, those who hadn’t received the right funerary rights, who were murdered or through acts of suicide would become the restless dead.

Open lock, end strife. Come death, and pass life – Scottish folk charm to urge death.

L. Stomma explored the restless dead who trouble the living. He noted they died at liminal times. Such as still-borns, women in labour etc. The astute among you will know Scottish folk-lore focuses primarily on liminality. It was at these liminal times folk were most worried about the interference of the daoine maithe – “the good folk” or the sidhe/sith. It’s no coincidence death is bound up in these times too.

An example that helps us grasp this idea of the liminal dead who are still alive is the poem entitled Sir Orfeo. In the poem Sir Orfeo travels to rescue his wife who has been taken by the king of the fairies. After going mad in the wilderness he sees her travel past in a fairy host and rushes after her. He finds himself in a new land. The otherworld [footnote] This is a very similar tale you’ll hear in Celtic Myth stories about the voyage tales. [/footnote]. Whilst there, Sir Orfeo notices the castle walls and impressive vaulted roof are made of the still living dead, most of them maimed and suffering.

These decapitated, asphyxiated, burnt and drowned were still alive. How is this so? The state of the dead demonstrates they didn’t die well. To the Scotsman and Irish man the dead would have been carried off body and soul by the sidhe. Phrases like “not one in twenty dies a true death, they all pass into another life” and “when a man dies, he does not die at all, but the daoine maithe take him away” show a belief of the dead being taken elsewhere. A different kind of death as we understand today.

Following in Sir Orfeo’s footsteps. We will explore a particular fear of a ‘bad death’, focussing on salient points to help us understand some of the current Scottish folk and funerary customs discussed later.

The Restless dead – Suicides in Rome, Norse and Scottish Cultures.

An example of a bad death cross culturally and temporally is the fear of suicides. I’ll focus on two different cultures that have affected Scottish belief, the Romans and the Vikings (Norse and Anglo-Saxon), and attempt to weave their influence into Scottish folklore.

The Romans viewed the dead as impure and dangerous. They offered to them to keep the dead in their good graces or prevent them carrying out misdeeds. In Rome, they called the restless dead larvae. The dead could cause misfortune, madness and disease. Madness was sometimes known as being ‘possessed by a larva’ (the word larvaetus used). These restless dead were the spirits of criminals, people who died in a strange and peculiar fashion, those who had died violently (except military), prematurely like suicide or had no tomb or place of rest, like those who had died at sea. The dead, such as suicide or criminals, were never entered into the houses of the dead and left to rot in a field outside the city, murder victims were buried where they fell or at cross roads. The dead who died without the constraining funerary rituals were destined to wonder restless and become larvae.

There were many of these dead wondering about. The father of the house who acted as “priest” for the family (pater familias) had to take steps to ward off the dead at the Lemuralia festival for instance. Throwing beans and striking a brass bowl was one way he could combat this incursion. [footnote] The brass bowl later became Iron as the iron age progressed [/footnote].

Cant find a Pulse … Broad Beans and the dead

The bean throwing is interesting. Why would someone throw beans at the dead? Beans were associated with spirits in Roman times. The spirits of the dead were said to travel up the hollow stems of broad bean, eventually maturing to a full bean. Each bean represented a spirit of a dead person. When a person ate the beans, they would release the spirt of the dead through their wind [footnote] This folk belief demonstrates one mechanism of how animism links the dead to the genus of a plant as in animism. [/footnote]. Farting was a sign the dead were escaping. Being quite gassy myself I chuckle at this idea that I’m full of spirits, but this was no frivolous concern to the Romans. Pythagoras died being trapped in a bean field afraid to step on the dead the plants represented to him as his murderers pursued him. Beans then came protective because people would leave beans for the dead as these represented other spirits they could take instead of their own. [footnote] Italians still eat Bean shaped cookies called “fave dei Morti” on the day of the dead today [/footnote].

Some suggest beans were relevant to the Celts in the same way. Archaeology has found a few pots filled with broad beans in Celtic age burial mounds that might be related to funerary rights. It is unclear and still only a hypothesis.

The dead & Crossroads

The Romans were powerless to stop the restless dead entering their homes on the unlucky days of the Lemuralia festival (the 9th, 11th and 13th of May) where spirits of the doorways conspired to let them enter. Another festival honouring the dead was the Roman Laralia festival. This was held at cross roads in Midwinter (the same as our Jol/Yule time) in honour of the lares compitales (the larva of the cross roads, hence the name Laralia). This feast of the cross roads was marked by the Pater Familias and not an official ecclesiastic. I think this is an important distinction. The pater familias hung wooden dolls (maniea) or bark masks (oscilla) from trees at crossroads. These represent fetishes the restless dead were meant to take instead of the real family member. Interestingly, Scotland has the Sidhe aboard at Bealltainn. The dates are very similar to the Lemuralia festival. La Bealltainn, Samhuinn and Yule are associated with the dead and the good folk/Sidhe. [footnote] Yule stemming from our Anglo Saxon, Norse Viking heritage [/footnote].

The cross roads are still a place in Scottish folklore where roads to the otherworld are said to be open. The influence from Rome could well be the mechanism and reason. We see later reference to “you shall make no binding, nor incantations upon bread, the herbs you would hide in the trees by crossing of two or three paths” (see the Capitula sub Carolo Magno, 744AD). Though not specific to Scotland it does testify to European wide belief that still existed in 744AD. [footnote] The Anglo-Saxons were also known to make incantations on bread “idols” so maybe a link here [/footnote]. Today, folk erect niches with Saints, many crosses or other apotropaic devices at cross roads. It’s an interesting hypothetical survival of belief from antiquity to today.

The fear of the departed suicide is present in Scotland a long time after Rome. Even around 1824. The tale goes … In Banff-shire a huge fight took place to prevent the burial of a suicide in the kirk yard. The strong men of the parish got word of the burial going to take place. Heading up before dawn and carrying strong sticks as weapons. They set up their place along the church wall and the strongest blocked the gates. Eventually, the suicides coffin surrounded by a drunk and similar angry crowd armed with sharpened spades arrived and the expected happened.

A struggle ensued trying to stop the suicide being buried in the churchyard. Many apparently “rolled into the dust” this day. Eventually the party carrying the departed suicide were kept out. The body buried close beneath the church wall. The lid was lifted before it was buried. Vitriol [footnote] an old term for sulphuric acid [/footnote] poured over it, dissolving the body. The smell made the crowd gag. The vitriol was used to stop the body being lifted during the coming night and returned to where their family lived. It was feared the departed would be placed against the front door to fall at the feet of the first person from their family to open it in the morning.

The idea no suicide should get a blessed burial is a common Christian belief. These dead would be unshriven or restless with no absolution. We have other stranger Scottish examples. Bodies of suicides were buried at the meeting of four cross roads, or at some other unfrequented spot resonant to our Roman ancestor’s practices. Through the suicides body a stake was forced. [footnote] The name “stake moss’ in Sanqhuar could be traced back to this [/footnote]. The Stake through the body was to stop the restless dead from rising ‘physically’ from the grave. This was a Norse and Anglo-Saxon belief too. You can read more about this in the MS from Rev’d Walter Gregor, 1874.

Folk believe nothing will grow over a suicides grave. Any pregnant woman who walks over it will lose her baby. Similar in the action of the sidhe ‘fairy blasting’ people or folks walking over ‘féar gortach’ (Hungry Grass)’. Hungry Grass was believed to be either caused by the faeries planting it or an unshriven restless corpse was buried in the vicinity of it [footnote]. Hungry Grass played a huge role in the famine in Ireland in the 1840’s. Another link between the sidhe and the restless dead. [/footnote]

The Norse and Anglo-Saxons believed the dead were said to wander around more at Jol (yule) but could do so at any time in the year. One mention in the Eyrbyggja Saga (chapter 54 – The death of Third Scat-Catcher) supports this:

“The morning that Thorod and his men went out westaway from Ness, they were all lost off Enni; the ship and the fish drave ashore there under Enni, but the corpses were not found. But when this news was known at Frodiswater, Kiartan and Thurid bade their neighbours to the arvale, and their Yule ale was taken and used for the arvale. But the first evening whenas men were at the feast, and were come to their seats, in came goodman Thorod and his fellows into the hall, all of them dripping wet”.

The Vikings believed the dead would return, not in spirt, but in person. It’s important to highlight the difference as there are examples I’d like to link to in the Scottish Death Customs of this happening at the wake. It will make more sense later if we emphasise this now.

Scottish Death Customs – Presaging death

There is a belief that death follows us, signs and portents are presented to us and death will rarely surprise if we know what to look for. Clans and families have a tutelary spirit that would have its own unique death signs and portends. The Most famous example of this is the keening of an bhean si (the fairy women). She would alert people (usually only those whose surname began with Mac or O’) death was coming. Other tutlery spirits might manifest differently with various signs from sounds, like dogs barking or bulls roaring, to lights and animals.

Interestingly in folk myth an bhean si (anglicised to banshee) originated from the death of a professional mourner, known as a keener or crier. Keeners were employed at funerals and wakes to mourn for the dead by moaning, chanting, crying etc. One account of this process is found in Patricia Lysaghts’ writing:

“she (the banshee) was one of th’oul criers. She didn’t say who she was, but it was always given down be people then, that the banshee belonged to the criers. Anyone that was at that in times gone by, it was left thet they’d be crying I suppose when they’d be dead. But they were called the banshees, everyone of them ye’d hear crying.”

In other folk belief the sound of bells in their ears, known as the “deid bell” was a sure sign of a coming death. There could be the sound of knocking, in sets of three strikes no human hand made [footnote] the origin of the term when “death comes a knocking” [/footnote]. Objects to be used at the funeral might be seen moving around the house or people would see lights, known as “deid cannels” following the future path of the funeral. Seeing a person’s double, known in Gaelic as a taibhse, was a sure omen of death to befall that person. Seeing the taibhse was a particular gift to those with second sight, or taibhsear. Others so gifted (or cursed) might see a grey mist about the head round a person soon to die, have a seizure inducing pre-vision of the funeral or would see them wrapped in their winding sheet. Other signs of death were linked to bird omens. Owls (cailleach-oidhche– the old lady of night – scots Gaelic) calling from outside your window or above your head a clear sign death was fast approaching. You can read more about this in Scottish Death Superstitions, Napier, 1879.

There are lots of cases found in Grimm of the similar beliefs of our Norse and Viking ancestors [footnote] Meyer’s version of Germon Mythology provides a list of over 2600 of similar superstitions [/footnote]. Death comes for you when your shadow is headless on Christmas eve, a candle goes out by itself in a house, or a board used to carry a dead man falls over.

A term used by the Vikings to describe someone who had a look of death about them expressed in the word feigr “destined to die soon” and even animals could bear this sign. What this looked like I have no record of. Interestingly, feigr links to the middle English word fey through etymology. The word fey is word used to describe fairies (or the sidhe) but also means the dead or doomed to die. Coincidence, I think not.

Scottish Death Customs – Laying out the dead

Great importance was attached to the proper observances around death. The first task a newlywed had was making her own winding sheet or shroud, for example. If she died without a shroud it would mean the death rites couldn’t be followed properly. The dead would find no rest. Restless dead weren’t a good idea as they would bring hardship, disease, madness and other havoc to farm and family.

Folk rites accompanying the laying out of a body have been preserved in various folklore records and followed a similar order. At the moment of death all windows were shunted open and iron was placed in any food stuffs, butter, cheese, whisky etc. least death infect them and remove the “toradh” (fortune) from them. Iron is the same protective measure used to prevent the sidhe. All the mirrors covered with white linen and all the clocks were stopped. The kirk said this demonstrated earthly vanity had no place for the dead and time was of no importance. [footnote] The covering of the mirrors could have other purposes. Some viewed mirrors as links to the other world but we have lost other meanings to the kirk [/footnote]. The bees must also be told about a death in the household. And sometimes the hives were turned away from the later procession with a veil over them. [footnote] There a lot of folk lore around bees being the messengers of deaths to the otherworld. [/footnote]

The body would be washed, dressed and cleaned. If the bed they died on had fowl feathers they would be placed on the floor. [footnote] There was something about fowl feathers that stopped the dead from finding rest. [/footnote] The body was laid out on a strykin beuird – a wooden board sometimes shaped like a coffin base. The wright of the village usually brought this board and the body was strykit, or laid on it, and covered in their winding sheet.

In similar fashion our Germanic ancestors would lay the departed out on a plank or stones. Close the mouth and eyes and clog the nostrils and anus with wax. The eyes were closed to protect those gathered from the evil eye. The blocking of the bodies holes was to stop the spirit and other body fluids from getting out. They were fitted with shoes called Helskor “the shoes of hel” to help them more easily move to the next life. These shoes are mentioned in the song the Lykewake Dirge. They are made reference to as ‘hosen’ and ‘shoon’. [footnote] We maybe see these shoes reappear in items buried in walls to protect the householders within [/footnote]

where they protected the departed on their journey to purgatory. The corpse was later taken out via a window or freshly made hole in the wall which was sealed up after. This was to confuse the stupefied dead from finding their way back.

Scottish Lowland Folk Magic Corpse Saining Rite

Records exist of corpse saining and Scottish folk magic blessing in the manuscripts. This example comes from lowland Scotland so may not pertain to the rest of Scotland. I offer this folk rite to preserve it but also to encourage you with its simplicity. It demonstrates how communities managed their own deaths with no ecclesiastic present.

Once the corpse has been washed and laid out in its shroud, one of the oldest women must light a candle and wave it three times around the corpse. [footnote] In a role reminiscent of the Roman Pater Familias, a “folk” priest but carried out by a woman, a mistress of ceremonies. This small folk ritual is a similar example to the sin eater. A sin eater was a poor man from the community who would eat the salt and the bread laid out on a corpse. Especially if a cleric couldn’t be found. He was often disfigured or disabled in some way and became a scape goat of sorts for a community’s sin. He would eat the sins of the dead so they could find rest. Here we have the idea of “restless dead” caused by sin and not activities from life as we have discussed before. This to me is a clear example of the glossing of an older belief by a Christian veneer. [/footnote] Then she must measure three handfuls of common salt into an earthen ware plate and lay it on the breast of the corpse. Lastly, she arranges three ‘toom’ or empty dishes on the hearth, as near as possible to the fire. All the attendants going out of the room return to it backwards repeating the ‘Rhyme of Saining’:

Thrice the torchie, thrice the saltie [torchie = candle, saltie = salt]

Thrice the dishes toom for loftie [loftie is praise I think so this would be – three times the dishes empty for praise)

These three times three ye must wave round

The corpse until it sleep sound

Sleep sound and wake nane

Till heavens the souls gane

If ye want that soul to dee [dee would be die]

Fetch the torch frae th’ Elleree

Gin want that soul to live

Between the dishes place a sieve

An it shall have a fair fair shrive. (Shrive is penance, so an easy penance)

This rite is called a ‘Dishaloof’. Sometimes (as is named in the verses), a sieve is placed between the dishes. She who is fortunate enough to place her hand in it is meant to do the most for the soul. Giving it a “fair shrive”. If all miss the sieve it augurs bad for the soul. [footnote] Sieves make an appearance in a lot of Scottish divinations rituals involving the future and the dead. [/footnote]

In other western counties, the dishes are set upon a bunker close to the deathbed and whilst the attendants sit with their hands in the dishes they ‘spae’. That is, they tell fortunes, sing songs or repeat rhymes. In the middle of which the corpse has been said to rise frowning and place its cold hand in one of the dishes. Presaging death to her whose hand was in that dish. This reflects on the traditions of the dead being animate post death. The connection of the dead to Speaing (fortune telling) is interesting one.

The candle for saining in this ritual should be obtained from a seer or Elleree [footnote] this term refers to a Saxon term for elder tree but also has connotations to someone with seer abilities in this instance. In Scots (Germanic influenced Scottish) the word Eller is also often the Alder (Alnus glutinosa), sometimes the elder. The word Elleree, n. means a person of preternatural insight; a seer. [/footnote] or from a person with ‘schloof’ (flat feet), ‘ringlit eyed” (With a great part of white in their eyes) or lang-lipit (thick projecting lips). These are all signs of being touched by the Sidhe/unlucky. However, dealing with death these persons were considered to be the luckiest. Here is another link between the dead and the Sidhe.

Mosstrooper’s [footnote] Moss-troopers were brigands of the mid-17th century, who operated across the border country between Scotland and the northern English counties of Northumberland and Cumberland during the period of the English Commonwealth, until after the Restoration. Much like the earlier Border reivers. [/footnote] led folklorists of the time to believe the saining candle should be made from the fat of a slaughtered enemy or at least from a murdered man. The candle must burn all through the night, on a table with a white table cloth covering it and for as long as the body remains in the house. The small round table the candles rest on may in no account be used for anything else. [footnote] Laws were passed in 1645 by the general assembly to prevent wakes being carried out because of how “messy” they got. Which had to be reinforced in 1701 because no one paid any attention to the original law. [/footnote] Other folk beliefs refer to them as Yule Candles. These special candles for watching the dead were the remains of especially large candles burned at Yule and extinguished at the close of the day. What was left of the candle was left preserved and locked away to be burned at the owners own “wauking” (wake). A nice link to the Yule festival and the dead and I think a more likely source of the candle than our Mosstropper’s murderer.

Scottish Death Customs – The vigil, The Sitting and Lykewake

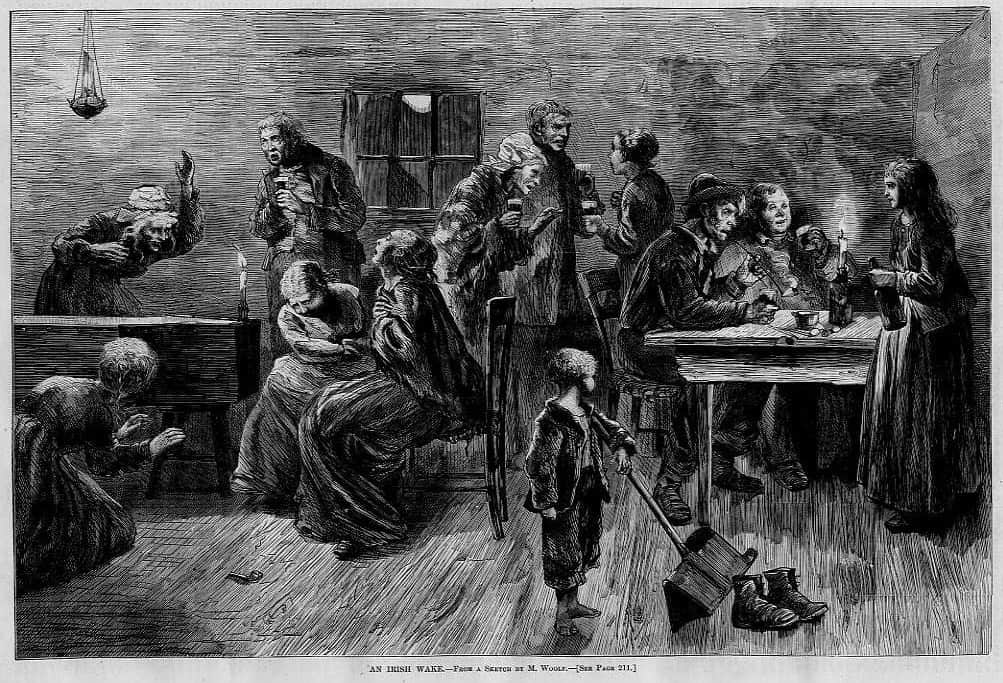

Envisage sitting over a dead body, lit only by two flickering candles through the night. Imagine the smell of putrid gas. An odd fart or burp indicating more gas escaping from the bloating corpse. Each gurgle and noise shifting its mass a little, almost like the body was still alive and moving. This was the situation with the vigil for the departed. The body was watched over up to 8 days, known as the dead days and things were far from sanitary.

This vigil could be known as a ‘sitting’ while the sun is above the horizon and a ‘lykewake’ after dark. Lykewake has it etymology in Germanic languages. Lyke meaning corpse and wake meaning to watch. [footnote]In Nordic and Swedish languages words for wake are still “likvake” and “likvaka” . [/footnote] A relative and a stranger must watch over the body. They could be relieved when they became too tired by another pair.

Things do not always go as planned on these occasions. Tales speak of the dead sitting up frowning, an unseen hand previously having moved the earth clod or dish of salt to the bedstead. Something had been omitted from the Saining, or otherwise, and the corpse was not happy. To help with the monotony, (and maybe fear), merriment, dancing, jokes, singing and games accompanies the Lykewake in Scotland. Those who were closet to the deceased would give food, drink, tobacco and snuff as required. This meant funerals and vigils could be expensive. Guests could and would get very drunk. Card games ensued. At times the coffin was used as the card table. It was not uncommon for the dead body to join in the games. A folk story suggests on one occasion, whilst a drunken game of hide and go seek was taking place. Some young men took the body out of the coffin and one of them hid in its place. When he was finally found he was quite dead and the body originally there couldn’t be found.

It’s important every watcher at the Vigil should touch the corpse with their hand. Said to keep them from dreaming of the departed. The kind caress and accompanying loving words would show they meant the deceased no harm. It also had another purpose. Our Viking ancestors were very worried about the dead coming back to revenge their murder. A corpse was said to bleed from its wounds when touched by its murderer. We see this repeated in King James I book, Demonology, – “In a secret murder if the dead carkasse be at any time thereafter handled by the murderer it will gush out of blood as if the blood were crying to Heaven for revenge”.

There would be a plate over the stomach of the deceased with a mound of earth in it or on occasion a small green piece of turf or salt. This was said to prevent the swelling of the stomach from gasses. This turf cutting activity occurs at other times – the passing over of farm property. In gallic this earth was known as Fad-seilbh, possession sod, infeftment; the sod or handful of earth given by the seller to the buyer of land. Saxon prayers to farmland and at the Riding of the Marches also featured earth. The ridings came later, though they are all undertakings based around liminality). I think the presence of the turf has a greater significance. One I can only guess at. The importance of the earth from the farm or land they worked would have been very important once people were no longer buried at the family funeral plot on the farm grounds. Maybe this was a way of keeping them in contact with it, but why?

Our Viking ancestors marked the vigil of the corpse in a similar fashion. Notes of vigils being accompanied by singing and dancing are recorded by Burchard of Worms. Jan de Vries, in Germanic Religion, Vol 2 mentions the Council of Arles (524Ad) who put it this way: “the laity who keep vigil over a dead person should do so with fear and trembling, and with respect. May no one risk singing diabolical songs, spinning or dancing as the pagans are wont to do under the devil’s influence”. The inclusion of spinning being carried out at the vigil of a dead person is interesting.

From the House to the Burial site – the procession

The funeral procession would occur in Scotland after the dead body was dressed in funerary clothes and then placed in the coffin. This part of the process was referred to as the “kitsan”. This could happen up to 8 days or more since the body had been laid out for the vigil. Sometimes part of the shroud or winding sheet was taken with a lock of the dead persons hair prior to the kitsan. This was then made into a napkin worn on communion Sunday or at other kitsans. [footnote] A “kitsan” is the funerary process from when the strykin beuird removed and the departed is dressed in their funerary clothes. [/footnote] Personally, I find this a beautiful piece of folk practice and wish we’d reinstate it, a memento mori of the most intimate kind and a link to our passed ancestry.

It wasn’t unusual for everyone to be pretty drunk from the time the kitsan took place to when the corpse was ready to go. “F’in the beerial wiz ready t’ lift”, i.e. ready to go, two chairs were placed in front of the door. The spokes, the rods used to carry the coffin, adjusted under it (there were usually 8 spokes for an adult).

A coffin, or a bier, or the spokes on which it was carried, was treated with especial reverence if made of the mountain ash.

| ‘A chraobh chaorrainn sin ’s an dorus, Theid thu fotham-sa dh’an chill, Cuirear m’ aghaidh ri Dundealgan, ’S deantar dhomh-sa carbad grinn.’ |

Thou rowan tree before the door, Thou shalt go under me to the burial place, My face shall be put toward Dundealgan, And a beautiful bier shall be made for me. |

The coffin was covered with a mort cloth (or plaid if the family were too poor). [footnote] The Mort cloth was provided for a rent from the kirk. The money from the rent going to the poor. [/footnote] The chairs were overturned once the coffin lifted off them and left there. These were only righted after sunset and after having been washed. If these chairs weren’t over turned the spirit might return to them. This would show proper procedure was broken and caused the dead to be restless.

On the “beerial lift” all the animals were loosed from the farm gates and driven along. It was not uncommon to see a funeral followed by baying cattle and was a mark of awe and reverence for the departed. Some funerals also had their own professional keeners that I’ve already mentioned.

There’s a copy of a keening song recorded below.

Some of the Lore states only men went to the ceremony and the women would stay at the house service. However, we have records of the first lifting of the Coffin being done by woman first then passed to men and pictures of women in wake processions. [footnote] I feel this may have been folklorist sexist interpretation [/footnote]. The body wasn’t taken through a field least it turned the field fallow. A similar power prescribed to the sidhe as already discussed above in hungry Grass. The funeral procession on no account took byways, but moved along the Kirk road. The road which the deceased had ‘walked to gods house must be the road he took in death’. Our Germanic ancestors had a very similar custom of treading the ‘path to hell’ and its mentioned in the Poetic Edda. [footnote] This is where we get the instruction in Scottish folk Magic to gather water from a March burn (a border stream) where both the living and dead have crossed. This stream would be found along the kirk road. This form of water in Scottish folk magic, Saining, dealing with the evil eye etc. is very common.[/footnote]

There were stones along the path called Restin stanes or small cairns built where the body was ‘rested’. If the Churchyard was a while away, (for rural communities it could have been a fair distance), or even if not, whisky would be drunk along the procession and at rest stops. The state of the funeral procession could be a pretty drunken mess from all the formal and informal drinking. Old scores were sometimes brought to light during the walk to the kirk. Broken faces and noses were not uncommon from fighting. Some processions so drunken and rowdy they managed to lose the departed in the snow on the way to the kirk. No one noticed till they went to inter the body. You can read a lot more about this in Death and Burial in Dumfries and Galloway, 1911.

Once at the kirk, the body might be rested at the Lychgate. Once rested the coffin would be taken round the kirk yard in a sun wise “deosil’ turn to their interment. Once the green turf was covering the coffin there would be another dram of whisky and folks would return home to the final part of the funerary party. Sometimes referred to as the Dyruge or dirge.

Funerary feasting

Archaeological finds of feasting occurring at the grave sites of Anglo-saxon burials suggest celebrations at the graves took place before kirk interference. The backfill on top of the corpse is filled with pottery, bone shards and other such festival related items. These celebrations took place before the Kirk stopped these activities demonstrated from the dating on the grave sites. It is clear from the evidence feasting at or near the grave whilst the body was still ‘fresh’ occurred often. More feasting should have taken place on the third, seventh and thirtieth day after the death of the person.

In Scottish funerary customs, after the funeral, bread and water were placed in the house where the dead person was held for the wake. This was in the belief the spirit of the dead would return to eat. If these offerings weren’t left for the dead, they wouldn’t rest. I find these two practices echo one another in intent though maybe not size.

Other death customs

In Denmark, it was forbidden to bury the dead in the clothes of the living. As the clothes rot the person who the clothes belonged to would waste away. You must not weep over a dead person or worse still allow tears to fall on them. To do so would cause the dead to be restless. If someone wasn’t dying very easily it was common to unlock the door. As they unlocked the latch they would say: “Open lock, end strife, come death and pass life”.

They would also turn pots upside down and open windows for similar reasons. This was to help the persons have an easy death and similar practices are found at births. There is a belief death only occurs at low tide and births at high tide. The water needed to be all the way out for someone to pass and all the way in for someone to be born. If you made it past low tide you would not go until the next.

The weather was auspicious over the dead days. A soft shower over and on the meels (or dirt) from an open grave would show the departed was enjoying happiness. A hurricane would happen if ‘some foul deed had been done and never brought to light’ or the deceased had a compact with Satan. In the case of those who were said to have other power than their own. A dove and a crow would battle it out over the grave making a dash to the coffin to see which one would make it first. Sometimes, it is said, they would fly with such force the bird would smash through the lid of the coffin.

Conclusion

In the Introduction to this series I highlighted the focus of Scottish Folk Magic on spirit and the dead and discussed how, because of this focus, it is different from other traditions. The activities carried out at funerals and around the dead reinforce the idea Scottish folk magic is related to the management of spirit and the dead. The world of the otherworld is largely one of the dead at these times. We have seen no mention of energy, astrology, or complicated ritual activities. No crystals and white lighting. There has been no chanting or calls to any god or infernal image, just simple folk traditions following the “right way of things”.

The role of the dead as active agents is definite. They could move around, give the evil eye and return to create havoc. Similar protective activities were carried out at funerals to safeguard the dead as to appease the good folk. Examples of using iron to stop the dead from spoiling produce, making offerings to make sure the dead were not angry and restless, using salt or earth over the body, lighting special candles and making sure activities are carried out in accordance. The role of saining is given importance, as is the number three, going deosil and liminality. Carrying out these protective rituals effectively and correctly least the dead return because of displeasure is the most important. All in all, practice for practice, the same tools and techniques are used to safeguard against the “fairies” in communities and at the quarter festivals as they are to manage the dead.

The role of the dead as active agents is definite. They could move around, give the evil eye and return to create havoc. Similar protective activities were carried out at funerals to safeguard the dead as to appease the good folk. Examples of using iron to stop the dead from spoiling produce, making offerings to make sure the dead were not angry and restless, using salt or earth over the body, lighting special candles and making sure activities are carried out in accordance. The role of saining is given importance, as is the number three, going deosil and liminality. Carrying out these protective rituals effectively and correctly least the dead return because of displeasure is the most important. All in all, practice for practice, the same tools and techniques are used to safeguard against the “fairies” in communities and at the quarter festivals as they are to manage the dead.

The significant role played by women as community lay priests and the disfigured or possibly disabled (those touched by the sidhe) is important. It is these outsiders who at the time of death were considered the luckiest and most able to help.

The amount of drinking and feasting that took place I think is also significant. It relates to the earlier celebrations formats such as feasting ancestors had thrown in the honour of their dead. To able to give someone a good death was important. It ensured they weren’t displeased and returned. The English writers who mostly captured this would have seen these folk customs as ‘uncouth’. The lack of piety would have unsettled them.

We have explored how the links between the dead and the idea of the good folk are intimately connected to one another. However, we have mostly done this through the lens of Norse/Anglo-Saxon and Lowland Scotland influences. It’s beyond the scope of an internet article to explore regional variances in more detail as there are sure to be variances that could be unpicked in highland more Gaelic focussed areas but they were not without their own Norse/Viking influences. Though not fully comprehensive, I think it provides enough examples to connect Scottish folk magic to the world of the dead and supports my original supposition and gives this element of Scottish Folk Magic more prominence within the corpus.

The next part of the series we will explore the suggestion the witch’s’ familiar was a departed soul. The links between the dead, the otherworld and what we have come to understand as the witch’s familiar will be explored and some witch trials examined to help bring some of this to light.

Footnotes below …

6 comments

Please tell me you are going to produce these articals as a book in the future. Just wonderful!

who knows ! Thanks for your kind words.

Thank you bb

Awesome!

Hi – I’m from Australia. I work in palliative care, and have been reflecting on the rites around death in “indigenous” culture. Clearly, the culture you are describing is indigenous to the landscape – in the same way as Australian first nations (aboriginal) people are indigenous to very specific regions within the Australian continent. I work in Wirajuri country, for instance. For these people, being returned to the land in which the arose is vitally important as part of their rites around death. Most want to die “on country”, and will often avoid potentially life-saving or prolonging therapy if that means they must travel, and may not die “on country” as a result. Dying on country is more important than living longer ‘off country’. I wonder whether the connection to the sod of earth in the death rites you describe arise from a similar sentiment. I have been told by my Scottish ancestors of the sentiment that “you do not own the land, the land owns you”; which has echoes in the Australian aboriginal understanding of a human being’s place in life and the connectedness to ‘country’. I wonder whether this custom is a reminder of the individual’s place (and the community’s place) within a specific landscape. Thank you for an enlightening series of discussions

Maybe ref the soil part … its certainly an interesting idea and thanks for your kind words much appreciated.