In this article

The skill of seeing into the future, divination, is synonymous with Scottish lore and tales. Spae wives looking into the tea leaves to folks with the second sight being visited by visions of things to come to pass. Folk practitioners in Scotland would often turn to animal accomplices to look to the future (such as the Fríth and animal omens). I’m in no way surprised to see the use of shoulder blades of sheep to see the future following in this cultural trend known as Slinneanachd/Slinnairachd or scapulimancy .

The role of the dead and spirits interest me greatly when it comes to Scottish folk magic. It’s not something we hear much of within mainstream folk writing. This practice fits the niche for a number of reasons. In this article we will explore the historical notes about Slinneanachd/Slinnairachd practice in Scotland and explore some direct quotes. It then goes onto look at the practice from another cultural perspective so we can maybe shed some light on how our ancestors would have done this.

Estimated reading time: 18 minutes

Slinneanachd/Slinnairachd

Slinneanachd (pronounced roughly as Slin-YOOR-hok) or Slinnairach (pronounced roughly as slin -YAR-hack) (as W. Thomas spells it) in Scottish Gaelic are words for divination by Shoulder blade. Slinneanachd is the reading of the blade or speal bone to foretell the future, also known as Scapulomancy.

Slinnairach/Slinneanachd as a practice not only highlights the role of animal sacrifice and use in Scottish folk magic. This practice also highlights the relationship and role of the butcher/Shepard/gamekeeper in Scottish folk practices and in our society.

Some background to the practice of Slinneanachd/Slinnairachd

We have records of the practice going back to 1815 from Sir Walter Scott and further discussed in1834 in the French Romance novel “Eustache le Moine”. William J Thomas in The Folklore Record (Part.1., 1878) goes on to explore the practice of Slinneanachd/Slinnairachd in more detail. The author of the piece discusses a conversation with Donal Macpherson who had this to say:

“Among the Druids, as among every other priesthood, Divination was reduced to a system. It is known that Rhabdomancy (dowsing with a stick or rod- ed), Geomancy (divination from the configuration of a handful of earth or random dots- ed), and Chiromancy (palmistry- ed) were practised among them. Whether Augury or Divination by the flight and chirping of birds was practised by them we cannot well say, though it is likely it was, as in some old tales we are told ‘ the birds once spoke Gaelic’ Of Haruspice, or divination by the entrails and other parts of the animals sacrificed, one remnant has come down to us pretty entire. It is unnecessary to quote Scripture in order to show that it was the practice of the Ancients to sacrifice on high places and in graves, as the numerous passages to that effect mentioned in the Old Testament must be familiar to everyone.”

We have to forgive some of the romanticism of the time relating to the 19th century romantic notion of the Druids. Donald Macpherson goes on to discuss the use of the shoulder blade in a related practice to Haruspicy which is divination by the shoulder blade known as “Slinnairachd”. From the Gaelic “slinnean” the shoulder and “àr” to slaughter/death and Àireach to leave us with Slinnairachd.

The custom of shoulder blade divination was, according to Donald MacPherson carried out on Nollig and Callawin. Christmas eve – Nollaig means “birthday” loosely and has become synonymous with the birth of Christ. Callawin seems to suggest New Year’s Eve. However, I can find no mention of the term Callawin in any dictionaries I have access to. The fact it has a w in it means it’s not a Gaelic word, as there is no W letter in the Gaelci dictionary. It might relate to the term caisean-uchd which relates to the breast strip of a sheep/goat killed at Christmas or on New Year’s Eve. The family woudl burn the breast strip of fatty tissue. The was passed between each member of the family as a charm against spirits. Thsi was never doen to protect from the fair folk according to Dwelly’s English Scots dictionary Mackenzie). It might just be a mis-transliteration of a term the author didn’t know how to spell so spelt it phonetically. It sounds a bit welsh to me… anyway … the dangers of taking old academia as truth are manifold…

We know New Year and Christmas held, and still do hold, special meaning to our ancestors regardless of the syncretisation occurring. These festivals held a traditional place for the slaughter of animals. This was also a traditional time where a sheep would be slaughtered and offered at this time by the Àireach (Àireach is an old title for someone who watches over the flock so a term for Cattleman, Grazier, Shepard, Bowman). Animals would have been slaughtered at this time of year for all manner of things. Food from their flesh, sinew for bow strings, hides and rendered fat amongst many other things. Animal use would have been very much akin to the use of gathering plants. Things would have been done cautiously and deliberately in respect to the animist nature of the culture. Dedicating the spirit of the animal to look to the future would have been another mark of respect given. It is clear the role of the Àireach filled a very important cultural role relating to our animist culture at one point the respect to the animal is still present even after a long time has passed between these cultures.

Other resources mentioning this practice can be found quoted below:

In Lewis divination by means of the blade-bone of a sheep was practised in the following manner. The shoulder-blade of a black sheep was procured by the inquirer into future events, and with this he went to see some reputed seer, who held the bone lengthwise before him and in the direction of the greatest length of the island. In this position the seer began to read the bone from some marks that he saw in it, and then oracularly declared what events to individuals or families were to happen. It is not very far distant that there were a host of believers in this method of prophecy.

-Isle of Lewis Folk-Lore (1895)

Thomas Pennant journeyed through Scotland in 1769 and recorded information about the speal bone. He states that,

When Lord Loudon was obliged to retreat before the Rebels to the Isle of Skie, a common soldier, on the very moment the battle of Culloden was decided, proclaimed (sic) the victory at that distance, pretending to have discovered the event by looking through the bone

– The Lore of Scotland, A guide to Scottish Legends. Sophie Kingshill

From the Gaelic Society of Inverness (Vol. XX, 1894). Though they mention wales there is some reference to the highlands:

“When the first great eruption of the sea in 1107 laid a wide district of Flanders under water, Henry I., who had obtained a power over Wales which was lost in King Stephen’s time, and not fully regained by Henry, planted several colonies of sea-evicted Flemings on the frontiers of Wales. One of these colonies was planted in Pembrokeshire, about Haverfordwest. Among the Flemings of that district, whom he praises for their hardihood and industry, Gerald met with a form of divination that was quite new to him. Here is his description of it Here is his description of it :—” It is worthy of remark that these people (the Flemings), from the inspection of right shoulders of rams, which have been stripped of their flesh, and not roasted but boiled, can discover future events or those which have passed and remained long unknown.” The strange thing to Highlanders, among whom slinneanachd was practised from old to nearly our own days, if, indeed, it has been wholly abandoned yet, is that the shoulder-blade sort of divination was not found by Gerald among the Welsh and Irish. In late times the Highlanders did not think it of much consequence whether the shoulder-blade to be inspected was that of a ram or goat, or even hare, but they thought the divination spoiled unless the shoulder had been boiled, and the flesh stripped off without letting the knife or tooth touch the bone. This mode of divination belongs to the sacrifice divinations of the Greeks and Romans. But both Flemings and Highlanders, who had far less connection with the Romans than the Welsh, might have inherited it from the Aryan ancestry common to Greeks, Romans, Celts, and Teutons.”

Gaelic Society of Inverness (Vol. XX, 1894)

We again see further mention of this in Wales and Ireland. Gerald of Wales, in Journey Through Wales (1188) wrote:

“A strange habit of these Flemings is that they boil the right shoulder-blade of rams, but not roast them, strip off all the meat and, by examining them, foretell the future and reveal the secrets of events long past. Using these shoulder-blades they have the extraordinary power of being able to divine what is happening far away at this very moment. By looking carefully at the little indents and protuberances, they prophesy with complete confidence periods of peace and outbreaks of war, murders and conflagrations, the infidelities of married people and the welfare of the reigning king, especially his life and death.”

Gerald of Wales, in Journey Through Wales (1188)

There is further mention of bone divination in Ireland, as recorded by Drayton in his Polyolbion, as described below:

“A divination strange the Dutch-made English have

Drayton in his Polyolbion

Appropriate to that place (as though some power it gave),

By th’ shoulder of a ram from off the right side par’d,

Which usually they boil, the spade-bone being bar’d,

Which when the wizard takes, and gazing thereupon,

Things long to come foreshowes, as things don long agone.”

A shoulder blade story

Donald recounts the following story about the practice that sheds some more light on it:

“The last man in the parish of Laggan who was skilled in Slinnaireachd died about 70 years ago. His name was MacTavish, and he had been many years Aireach to Mr. MacDonald, of Gallovie. There are many wonderful stories told of this man’s skill in his art. The following I have often heard related, and once by a man worthy of credit who averred he had been an eyewitness to it. The fame of MacTavish had travelled to distant parts of the country, and, having come to the ears of a rival diviner, the latter determined to have ocular proofs of his proficiency. For this purpose, he took a journey of many miles, and on his arrival at Gallovie announced his errand, and was directed to the house of his brother soothsayer, where of course he was made heartily welcome. Mr. MacDonald invited several of his friends to dine with him on New Year’s night and took care to have the two diviners of the company.

After dinner a shoulder-blade was presented to the stranger, and he was requested to declare the result of his inspection, be it good or bad. After having pored over it for a certain time he was observed to change colour, and at first, he refused to tell what had so affected him; but when pressed, he positively asserted that someone should be hanged on that domain before morning. The company were of course variously affected by this declaration; some believed it and were alarmed; some did not but had good manners enough not to turn it into ridicule. They however agreed in one thing, to let MacTavish re-inspect the blade.

He did inspect it, and declared his satisfaction at the skill discovered by the stranger, but added that he had made a slight mistake, for that the ill-fated creature that was to be hanged could be no other than the devil himself, for that it had horns and hoofs. ‘ But,’ said he, jocularly, ‘ no doubt my friend also has discovered these Satanic characteristics, though politeness towards two of the present company has induced him to conceal the fact;’ and he bowed to the minister of the parish and to a Catholic priest who happened to be present. The night passed; but early on the next morning, as MacTavish went his rounds, he found a favourite yearling bull hanged and quite dead. He had put his head through between the bars of a ladder, and, as he was struggling to free himself, the heavy ladder fell across a deep foss, over which the animal was left suspended.”

What does this mean in terms of practice?

The tales and the stories and direct quotes highlight a few interesting areas of thinking.

The purposeful slaughter of the sheep in the name of the person who the practice was to be carried out for was important. This sacrifice in the name of a person would be step one.

It suggests a role for the Butcher/Cattleman Shepard, found in the title Aireach reflected in Slinnairachd. Aireach means someone who watches over the cattle and they would traditionally been the people who also slaughtered the animals.

There is some discussion of linking the Àireach to similar Gaelic words. William Thomas (1878) Links Àireach to a high place in Scotts Galeic (àirde) and to the term àr to slaughter/death and Ara, an altar. I can see no evidence for this exploring the etymology of the words (àra means kidney for instance not an Altar or is a plural or àr – slaughter) but etymology isn’t my strongest skill set..

The evidence we do have does ascribe a role to those who watched over the cattle. The tales all suggest these individuals would be the ones who carried out the soothsaying on behalf of the named person. The role of Shepard as transgressor and folk magician also relate to the lore (but this is a discussion for another day).

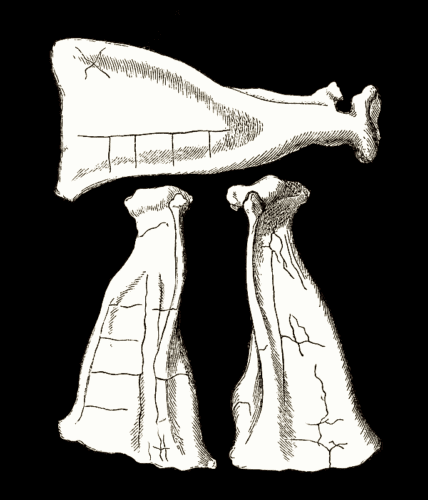

How to carry it out

Once the Sheep had been killed in the name of whom the fortune was to be told for. It would be cooked mostly by boiling it by quite possibly over a fire. The flesh would be removed from the shoulder blade bone without any use of metal. Folks use a bone, a wooden knife or their teeth. Why no Iron? Sir Walter Scott (1815, MS. Advocates Library) suggests the use of “iron hinders all the operations of those that travel in the Intrigues of these hidden Dominions”. Once the flesh has been removed, people would hold the blade up to the light and look for signs that would dictate the future. Donald MacPherson goes on to suggest “Nothing can be known that may happen beyond the circle of the ensuing year. The discoveries made have relation to the person for whom or by whom the sacrifice is offered of the one whose blade was to be read in the name of.”

The cooking of the shoulder blade would have resulted in a series of cracks and other discolorations due to the thickness of the shoulder bone. This has been further expanded up on by T.F. Thiselton-Dyer in Domestic Folklore (1881) when exploring Spatulamancia. Here Thieslton-Dyer suggests a long split lengthwise is known as “the way of life” and cracks to either the left or the right of this would donate different kinds of good or evil fortune. A clear shoulder blade would suggest a future free from strife, marks or spots or other discolouration’s depending on what side of the shoulder blade they occurred or where abouts would indicate different things.

The orientation mentioned of the blade to the longest part of the land “who held the bone lengthwise before him and in the direction of the greatest length of the island. In this position the seer began to read the bone from some marks that he saw in it.” Is really interesting to note especially given the example that will follow.

Examples of shoulder blade divination from other cultures

This form of divination exists across continents and countries and can be found in China, Greece, Chukhee Peoples and in Samí cultures and many more.

The example I’m drawing on here is from the Chuckee People. The Chuckee people are an indigenous people inhabiting the Chukchi Peninsula and the shores of the Chukchi Sea and the Bering Sea region of the Arctic Ocean within the Russian Federation.

We sadly need to look elsewhere to recreate this due to the scant information we have on our own practices. There are a number of practices to draw. I am by no means suggesting a straight copy from what follows. You will see when you read through the following the precise use of the shoulder blade has been adapted to the landscape and culture of the Chukhee peoples. I’m exploring these ideas, not to appropriate, but to explore how a land and sea-based people (much like the Scottish) employed shoulder blade divination and to explore similarities. I hope it might help those inspired to pursue this practice from a Scottish perspective to take inspiration from what follows.

The below is paraphrased from Memoirs of the American Museum of Natural History, Vol. XI By W. Bogoras (1904)

“The Reindeer Chukchee use for divination only the shoulder-blade of the domesticated reindeer. The animal, in most cases, is killed for this particular purpose (compare with what we know about Scotland- ed), though the bones of every reindeer brought for sacrifice, or slaughtered for meat, are also fit to be used. The bone is taken raw, and the meat carefully cleaned from it. Then a small piece of burning coal is kept close to its centre. It is fanned, by means of blowing or light swinging, till the bone is carbonized, and gives the first crack. After the performance, the burned place is immediately broken through and reduced to crumbs, but the bone itself is added to the common kitchen-stock used for trying tallow. During the fall, the shoulder-blade of the left side is used for divination in personal or family affairs, while that of the right side is called “alien,” and used for divination in the affairs of other people. During this period, divination is employed, first, when changing camp after the first fall of snow, then again about two months afterwards, when moving into winter-quarters.”

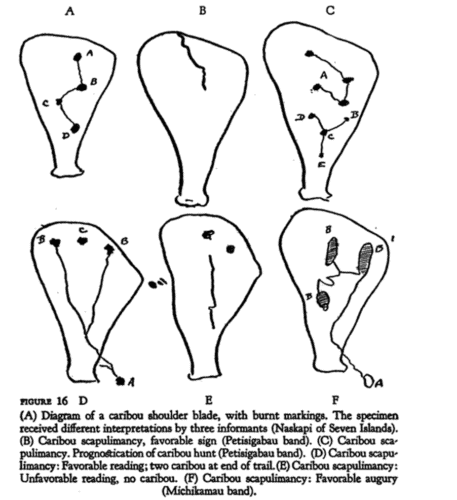

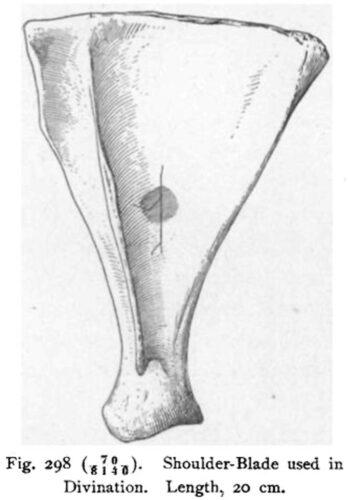

In explaining the lines of the cracks, the shoulder-blade must be kept with the broad part upwards (see figure below) (compare with the orientation of the bone mentioned in the Scottish sources). The ridge in the middle is called “mountain” (ičvui’gin) and is considered to represent the mountains and the inland generally. All the lower part of the shoulder-blade beneath the burned spot is called “bottom of bone” (a’3mhê) and is considered to represent the underground countries. The outer edge of the shoulder-blade, all around the broad part and down to the very bottom, is called “sea” (a’ñqA), and is considered to represent the seacoast.

“Usually one vertical crack is formed, with various ramifications above and below. The following principles are applied for their explanation. Everything that comes from the sea is good, even though it be from under the supposed level of the ground: “Nothing evil comes from the sea.” Indications from the underground, or “bottom of the bone,” on the contrary, are of evil character. From the mountain above the level, there may appear indications of either in kind, good or evil.”

“If there is produced only one vertical line, it is a favourable indication; but if this line is short, or, on the contrary, if it reaches the very edge of the bone, the indications are unfavourable. Should the bone burn too quickly, it is likewise unfavourable. The small crosslines not reaching up to the principal crack, when in the upper region, foretell only news of something; while the longer lines, crossing the principal crack, foretell the arrival of the thing. A large cross zigzag line foretells greatness of the thing which will come. For instance, a detached crossline from the “mountain” may signify news about wild reindeer; a longer line, the coming of wild reindeer; and a zigzag line, the abundance of the wild reindeer; etc. A crossline from the “bottom of the bone” foretells an attack by wolves, or the arrival of the “spirit of disease,” or even death. A line formed on the top of the principal crack signifies a snowstorm; a semi-circular line on the same place signifies unexpected death. A detached line in the region of the “sea” signifies some unexpected news. Thus, for instance, cracks on the shoulder-blade represented in Fig. 298 indicate (1) abundance of some game coming from the mountain, evidently reindeer, because it was the season for the reindeer-hunt; (2) the coming of wolves to the herd of the camp.”

“In performing divination regarding the direction of moving, the person must first select a direction, and then inquire about it. If the indications are unfavourable, — that is, if some evil is indicated as likely to happen on the journey, — the proposed direction is abandoned. In this case the shoulder-blade itself is immersed in a mass of stuff emptied from the reindeer-paunch, which is generally considered as highly effective for ceremonial cleansing of this kind. While immersing the bone, the person says, “This is not my shoulder-blade: this is an ‘alien’ shoulder-blade.” Then the bone is left sticking in the stuff. On the next day another reindeer is killed, and the divination resumed for a changed direction of the route. This is watched with the keenest attention, lest, through some carelessness, the true meaning should be misunderstood”.

“An unfavourable indication of a shoulder-blade may be tested by divination with the sinew of a reindeer-leg. A piece of sinew is wound tightly around a splinter of wood several times. If it unwinds quite smoothly, this is considered a favourable sign, and the indication of the shoulder-blade may be rejected. If, on the contrary, it becomes entangled, this corroborates the indication of the shoulder-blade, and some reverses are likely to happen. Then another shoulder-blade may be tried for some other direction of moving”.

The above is directly quoted from the source linked above. We can see many similarities to the Scottish sources, and I can imagine there were certain indicators folk used in the highlands with a similar basis of consideration.